At I Can for Kids (iCAN), we’re often asked why immigrants and refugees experience food insecurity after they relocate to Canada. Even though we’ve responded to this question by summarizing the latest research in a recent blog, we also wanted to share insight from Newcomers who face this struggle. In this blog, we interview Diego, a young man who immigrated to Canada at age 14 and now works for one of our corporate donors. We’d like to thank Diego for sharing his unique story of navigating food insecurity as a child. In two different cultures and in two different countries!

Q: Diego, what inspired you to talk with us about such a difficult experience in your childhood?

By sharing my personal story, I hope to bring attention to the incredible role food has in a kid’s life as a source of connection, tradition, and safety. I’m an adult who experienced food insecurity as a kid. Twice! I’m not sure a lot of people understand how food insecurity can lead to long-term consequences well after a child grows up, even if that person is no longer food insecure as an adult. I thought it might help your audience to better understand the dignity and impact of your program if they had the chance to see this issue from a new perspective.

Q: When did you first experience food insecurity?

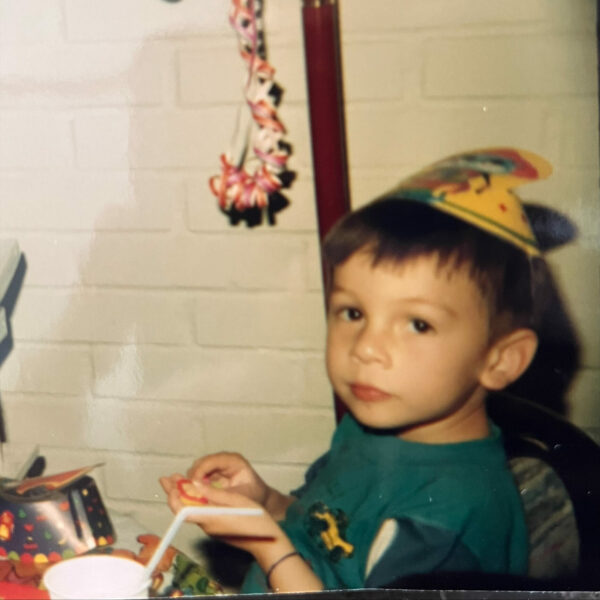

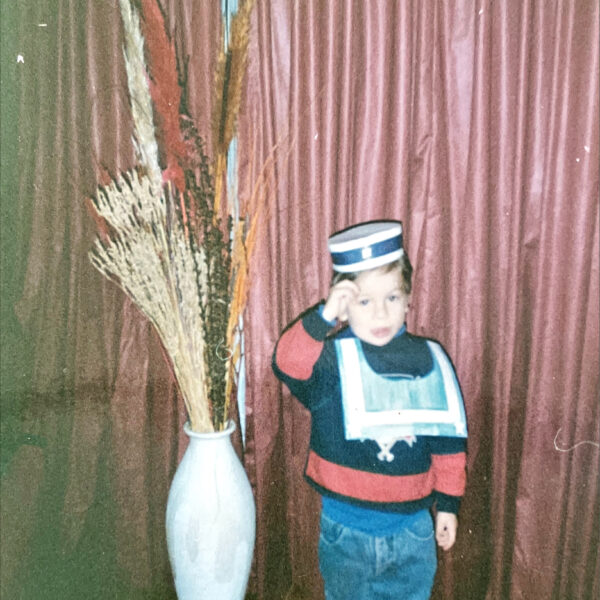

My first experience with food insecurity was as a young child in Chile. Our country had an unstable economy in the 90s , and that meant my parents struggled to fill our fridge even though we were a middle-class family. They were bankers, and they still couldn’t make ends meet. Inflation pushed many of us to the fringe and their wages were simply not enough to keep up with the cost of living. They had to make a lot of tough decisions, like choosing to pay our utility bills or cut back on food for me and my younger sister.

I remember my parents explaining that they just couldn’t buy me the same foods that I saw most of my classmates eat at school. We always had to choose just the basics and we could never afford higher-quality products. They were so frustrated by their lack of control because no parent wants to tell their kids that they can’t afford food. I grew up witnessing the stress and anguish that food insecurity forced upon my mom and dad.

Q: How did your family try to cope with food insecurity in Chile?

At that time, Chile didn’t have community or government programs to help food-insecure families. My parents got through challenging times by leaning on the support of relatives and people in the community who had stronger finances. Struggles around food just came up as natural conversation. People would just ask: “How can we help you?” In Chile, everyone knew that food insecurity was a money issue and that many families faced this problem.

Times were tough for everyone because we all had to deal with a system-wide problem that didn’t allow for a good standard of living. Food insecurity was never associated with laziness, and there were never any negative assumptions about why my family couldn’t afford enough food. I had an unmarried uncle who helped a lot because he had much lower expenses with no children to support. He and many others helped us because they genuinely cared. Their solidarity made those years much less scary and isolating.

My family also did as much as we could for other food-insecure families. We’d take care of their kids after school and give them snacks so their parents didn’t have to pay for childcare while they worked. In fact, none of us ever knew who would suddenly need help with food because everyone’s financial situation constantly changed, especially if they had to pay for unexpected expenses like home or vehicle repairs.

Still, food insecurity was a big part of what inspired my parents to look outside of Chile for more stability and a better life.

Q: So that leads to your life in Canada. What caused your family to experience food insecurity here?

We arrived in Calgary with just a few clothes and even less money. For the first three months, my parents couldn’t earn any income because the government needed to process their legal work permits. So, we had to use up what little savings we had to survive. My parents were limited to low-paying and entry-level jobs since they didn’t have any previous Canadian work experience. Their combined incomes weren’t enough to afford all our expenses and we had to look for other ways to get enough food and clothing.

Q: How was the experience of food insecurity different in Canada compared to Chile?

Unlike our life in Chile, we had no community or family to support us in Calgary. This made the experience of food insecurity much more isolating. We didn’t know who to ask for help and we didn’t want to tell everyone that we needed support. My sister and I hid a lot of our struggles to help lighten the load on my mom and dad who were doing the best they could to shield us from money problems. Our parents only knew the surface of what the two of us were going through because we hid the frustration and the shame, especially as teenagers.

In Canada, people think food insecurity is caused by a personal flaw or a lack of motivation or not knowing how to manage money. They don’t realize how easy it is to become food insecure when there are so many factors that are out of your control. We couldn’t afford a TV, so we just didn’t watch TV. But food is never transactional like that. It’s life. It brings you joy and connection. We didn’t know who to ask for help. We had no idea how to navigate the system to figure out the social services that were available.

Q: How did your family try to cope with food insecurity in Canada?

As an immigrant, you have no choice but to ask for support because you don’t know how to navigate all the new systems. Its’ very challenging to ask for help from strangers versus people who know you and love you. We felt very vulnerable as immigrants because we wanted to show how much we appreciated the opportunity to live in Calgary. We did not want to feel like a burden on the system and we felt wrong asking for help. Additionally, the language barrier and our lack of understanding of how to navigate Canadian institutions was intimidating.

Like many new immigrants, we were referred to the food bank. We were grateful to have this support because it was our only regular food source. Nevertheless, we soon faced big challenges due to the unpredictable food options and the struggle with transportation. The contents of the hampers varied a lot every month. This meant my parents often had to ignore our traditional ways of eating and try to create meals from unfamiliar foods, like canned goods and convenience items. Due to the predominantly non-perishable nature of donated food, we didn’t always receive fresh produce, or we received random vegetables and fruit that didn’t always align with Chilean cuisine.

Another major struggle was how and when we accessed the food bank. We didn’t have a vehicle, so we had to pay for the bus or a taxi to get the hampers back home. Transportation logistics were always very stressful, especially during the cold winter months when we couldn’t afford proper clothing to withstand the low temperatures. Most of the time, my parents had to miss work while my sister and I had to miss school to help our parents pick up the hampers. Accessing food was challenging and frustrating. It felt disempowering when we weren’t able to provide for ourselves. However, the hope of eventually being in a better place without the need for support is what kept us going through this challenging time.

Q: What did you experience as a kid in school who was food insecure?

Well, my peers didn’t know that I was going to a food bank. They would just comment on what I was eating without understanding that I had no choice. I often had to eat canned foods like soups or stews and the other kids would always ask why I liked eating that stuff. I wasn’t going to share with them why I was eating that way. Kids are very curious about what their friends are eating. We’d always sit in a circle during lunch, and everyone would look around to see what everyone else was eating. I learned very quickly to hide certain details about what I was eating because my experience with food was very uncommon amongst my peers.

That’s a key reason that I am so close to my sister. She was the only other person I could talk with because she experienced all the questions as well. We didn’t want to tell our parents and add to their stress and make them feel bad. We knew it could be way worse. We just craved meals that would remind us of our home in Chile. Tasty and familiar food is a little piece of home, and it would really reduce our stress when times were rough in Canada as we struggled to adapt to a new country and a new culture.

Q. I’m beginning to understand why you had such a strong reaction to the I Can for Kids program when you first met us through your work. What were your initial thoughts when you heard about our grocery gift card approach?

Well, I realized how I Can for Kids makes sure food-insecure families can access food that works for their diets at the store they like and at a time that works for them. Instead of being forced to work around the donated food we received in hampers, my family could have used gift cards to work food into our life and culture. I also realized that we could have chosen to go grocery shopping when the weather was good! We could have saved money on transportation and my parents could have bought the food after work rather than taking time off and losing income.

Food is a way for a person to sooth themselves, find some calm, and even add a perk to their day. Grocery gift cards would have given us much more security around knowing that we would have enough food, and food that we would always enjoy. Food security means way more than just having access to food. It means being able to get the food you truly want in a dignified way. Food insecurity is never a choice. And everyone experiencing it yearns for the day they will be able to support themselves. Food insecurity is always isolating. And the I Can for Kids program ensures dignity and freedom for families struggling to afford enough to eat.

Q: You mentioned long-term consequences of food insecurity. Are you willing to share more about that?

Well, when my family would shop for groceries, we couldn’t afford the good cereals. We couldn’t afford yogurt. I learned that I couldn’t have what I wanted. I still see food the same way, even though I now have enough money to buy what I want. I can see how a gift card would have made me less apprehensive to pay a bit more for better quality products, like fresh foods from Chile that cost more here.

I still carry several behaviours with me today that I developed when I was food insecure, while other habits I was able to overcome with time. For example, I struggle to eat everything on my plate. I always save something because that way there will always be leftovers guaranteed for later. I also struggle to indulge with high-quality food even though I can now afford it. For a long time, I was reluctant to join friends in restaurants, and when I did, my tendency was to always order the cheapest meal even if I’d prefer something different. I have the tendency to buy the cheapest version of every product in the grocery store, and won’t even allow myself to buy something that costs just a dollar more when it’s better quality.

I constantly try to balance out the best nutritional choices versus the most affordable options. I want to buy healthier foods but there are times that I override this desire due to cost. Sometimes I’m worried and self-conscious that I am consuming more than what I need. What if other people need it? I’ve also noticed that my parents have gone in the opposite direction. They now buy too much food, so we’re all trying to find a balance with the abundance of choice we can now afford.

Q: What encouragement would you give to new immigrants who are struggling to make ends meet?

I would first say to them that whatever difficult moment they are going through, it is not permanent, things will get better even if it doesn’t feel like it right now. I never forget where I came from, and through my memories of those experiences as a newcomer to Canada, I know the feeling of helplessness when there is a need to be met and no money to fill it. It takes strength and courage to ask for help. It’s not a personal flaw or a failure to reach out for support; it’s a stepping stone to get to a better place. You are not alone and while those who have not seen struggle in their own life will likely not understand the struggles of others, many are there to help. Your struggle isn’t about poor life decisions. You just need time to make new connections and adjust to your new life. There are many programs and many people who are willing to help. I would encourage you to be willing to feel a bit vulnerable and ask for assistance.

Q: I’d like to fast forward your story to today. How has your life evolved?

It took my family about five years to stabilize and become food secure. My father was able to raise his income because he entered a whole new career in commercial painting for large corporations. He eventually started his own company! My mother became a nanny because she has a background in preschool education from Chile. She taught kids Spanish. I’ve just finished a bachelor’s degree in communications and I now work in the area of corporate giving and social impact. My sister is currently completing her master’s degree in ecotoxicology with the goal of finishing a Ph.D. in ecology.

Even though we were food insecure for the first part of our new life in Canada, it was still worth it to move here. In Chile, it felt like our quality of life would never truly get better. But in Calgary, we could always sense the steady evolution of our situation. We always felt like there was a continual progression and that things would eventually get better. And they did! Once my parents reached solid footing, it was an incredibly happy day knowing we would no longer need to request food hampers.

Once again, thank you Diego for sharing your powerful story. Most people born in Canada experience little opportunity to discover more about the complex and emotional journeys of the immigrants and refugees who choose to make our country their new home. We greatly appreciate your courage to demonstrate the formidable role that vulnerability plays during efforts to foster more dignified changes across our society.

While iCAN continues to promote better income policies to prevent food insecurity altogether, it’s always encouraging to realize how donations to our grocery gift card program still make all the difference in the lives of many kids from diverse families across our city.

To join iCAN’s expanding list of champions, check out the ways you can get involved or donate.

To learn more about I Can for Kids and their unique approach to childhood food insecurity, visit www.icanforkids.ca

About Donald Barker

Donald Barker has worked as a registered dietitian for more than 25 years. He also has a professional background in communications and has long advocated for populations who face adverse, unjust, or systemic barriers that lead to higher rates of poor social, mental, emotional, and physical health outcomes. Donald currently volunteers as an Advisor with iCAN to support our transition towards evidence-based approaches that help improve the well-being of children in Calgary who live in low-income and food-insecure households.

About I Can for Kids Foundation

I Can for Kids works closely with multiple agency partners to target and distribute grocery gift cards to food-insecure families who are most in need. The iCAN grocery gift card program is a more dignified and inclusive approach to dealing with food insecurity, allowing families to shop where everyone else shops and to choose foods that are appropriate for their health and cultural needs. Explore their website to discover more about iCAN’s impact over the years.

For more information and media inquiries, please contact iCAN Executive Director, Bobbi Turko at bobbi@icanforkids.ca.